In part I of this series I talked about conventional production and how decline rates were catching up to years of under-investment. I argued that the world was betting almost entirely on US Shale and OPEC to meet the world’s oil demand growth in the next few years.

In part II I talked about why US Shale is unlikely to meet such growth expectations. I described what I consider to be structural flaws in the US Shale business model and concluded that a slowdown in US production growth was not a matter of ‘if’ but ‘when’.

In this article I want to talk about OPEC 2.0 (OPEC + Russia). In the absence of robust US Shale growth, the world will be relying solely on OPEC 2.0’s spare capacity.

First, we should think about how much spare capacity there is, and where it lies. According to the IEA, OPEC spare capacity is around 3.2mm b/d. Saudi Arabia (currently producing slightly less than 10mm b/d) claims it can take production to >12mm b/d if needed. However, based on independent third-party assessments from people familiar with Saudi Arabia’s oil fields and geology, producing at >11 mm b/d is likely not realistic as it would strain the oil fields and reduce ultimate recovery. 10.5 mm b/d is probably a better estimate for sustainable production. This is supported by trends in Saudi inventories during the Q4 2018 supply surge and the Abqaiq attacks (Saudi production appeared to be 11mm b/d+, but in reality they were selling oil out of inventory).

BCA Research (a prominent macro / commodity research firm) wrote the following in 2018:

“We have long believed KSA’s ability to maintain production above 10.5mm b/d for an extended period is suspect, despite its claims it can ramp to its capacity of 12mm b/d. We are carrying KSA’s current production at 10.4mm b/d in our balances estimates, roughly the level it self-reported to OPEC last month. To be clear, we are not saying KSA’s production cannot be increased – perhaps to 10.7mm b/d – but we are dubious it can get to its claimed 12mm b/d capacity, or that it can sustain 10.7mm b/d indefinitely.”

The remaining ~900K b/d of core OPEC capacity is largely with Kuwait and the UAE. Iraq and Angola have some, but are pretty much maxed out. Russia has an addition 300 – 500K b/d. Bringing this all together, there is around 1.8 – 2.6mm b/d of spare capacity with OPEC 2.0 (Saudi Arabia 500 – 1000K b/d, Kuwait + UAE: 900K b/d, Russia: 300 – 500K b/d, Others: 100 – 150K b/d). This represents 2-3% of the current annual oil demand.

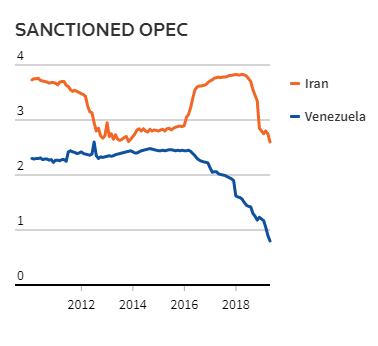

Leaving aside core OPEC + Russia, we have the sanctioned category:

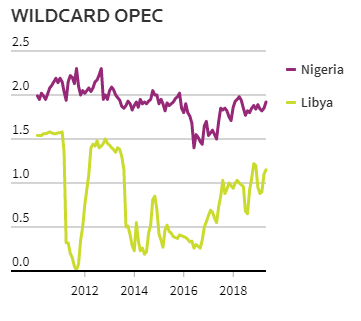

And we have the wildcards:

It may seem that 2-3% spare capacity is more than sufficient. But keep in mind that:

1. Oil production outages from core and non-core categories represent a significant risk.

A large percentage of oil continues to come from volatile regions that are subject to political and economic shocks. As discussed in Part I of this series, the sanctioned category is unlikely to bring significant production online in the next year and in fact represents further downside risk if the economic situation in those countries deteriorates.

The assassination of Iran’s military leader Soleimani has dramatically escalated tensions between Iran and the US. Iran could retaliate by attacking Iraqi oil facilities being operated by US personnel and the US could respond by attacking Iranian oil infrastructure.

Similarly, Libya is in the middle of a civil war and its 1.1mm b/d of production remains at risk. The battle for the capital Tripoli between forces loyal to eastern commander Khalifa Haftar and those loyal to the internationally-recognized Government of National Accord rages on.

Meanwhile deepwater OPEC players like Nigeria and Angola are likely to face declining production due to capital constraints. Nigeria has had its own share of problems fighting militia in the Niger Delta that often threaten to attack oil rigs.

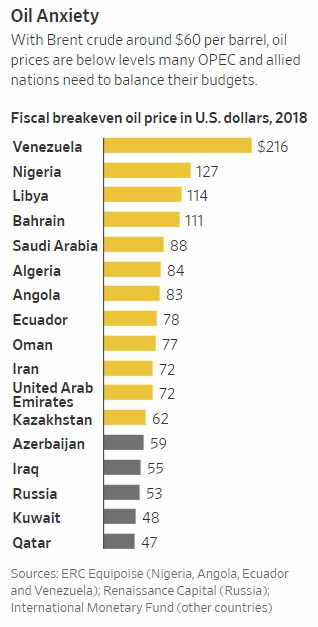

2. OPEC countries are incentivized to keep oil prices high to support their domestic economies (which rely heavily on oil revenues)

Most of the major OPEC producers need $70+ Brent to balance their fiscal budgets.

Saudi Arabia, the most important OPEC member, has one of the highest rates of working-population growth. 25% of Saudi Arabia’s population is between the ages of 15- 24. The Saudi govt. remains the only meaningful employer and needs significantly higher oil revenues to support the level of job growth needed to prevent youth unemployment.

The Aramco IPO is a big part of this long-term economic ambition. MBS’ goal with the IPO was to monetize a significant percentage of Aramco and use the proceeds to diversify the economy away from oil.

Unfortunately, the IPO was not as successful as the Saudi govt. had hoped. International investors balked at the valuation and the offering ended up being a much smaller, domestic-only affair, raising only a quarter of the intended level of proceeds (~$25bn vs. $100bn). What this means is that the Saudis will need to continue selling shares in the coming years in international markets to raise the desired level of proceeds. Sustained higher oil prices will be critical to support Aramco’s market valuation and attract additional investor interest.

Based on the research I’ve read on this topic, the Saudis need $80+ Brent to achieve their 2030 vision ((https://vision2030.gov.sa/en) and $90+ to eliminate their budget deficit.

Conclusion:

While it may appear that OPEC has sufficient production growth capacity for the next year or two of oil demand growth, the reality is that OPEC is likely to reserve this capacity for future oil outages, as well as to keep oil above the required fiscal breakeven price. The recent OPEC agreement to extend and deepen production cuts is strong evidence in support of this (https://www.cnbc.com/2019/12/05/opec-december-meeting-opec-production-cuts-in-question.html).

Iran and Venezuela remain politically and economically constrained. And while they may bring an additional 1-2 mm b/d of production in the coming years, it will likely be too little too late.

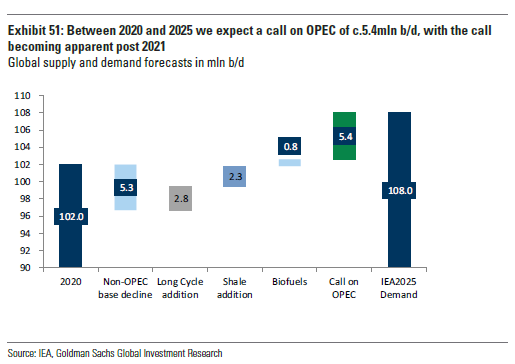

I will write a final piece in this series on demand growth, but let’s just take IEA’s demand numbers at face value for some back-of-the-envelope math (IEA is notorious for underestimating demand and then revising it upwards later).

Based on IEA’s 2025 demand projection, OPEC will need to produce 5mm b/d+ more in the face of slowing US Shale growth to balance the market over the next 5 years.

Let’s be conservative and take the upper-end estimate of core OPEC spare capacity of 2.6mm b/d. Let’s then assume the extremely unlikely scenario of Iran and Venezuela production doubling from current levels. As you can see, even if we push spare capacity to effectively zero, OPEC will struggle to meet this call.