I’ve been following the inflation debate quite closely this year and thought I would pen my thoughts down. Friday’s CPI report showed that inflation in the US had moved up to 6.8% YoY, while core inflation (ex food and energy) was ~5%. These are the highest numbers since 1982 and 1991 respectively. Since April this year, YoY inflation has been >4% while core inflation has been >3%.

The US government and the Fed continue to insist that the drivers fueling inflation are ‘transitory’, including one-time base-effects (2020 base numbers ‘artificially’ low due to the economic impacts of COVID-19), and have kept fiscal and monetary policy in expansive mode.

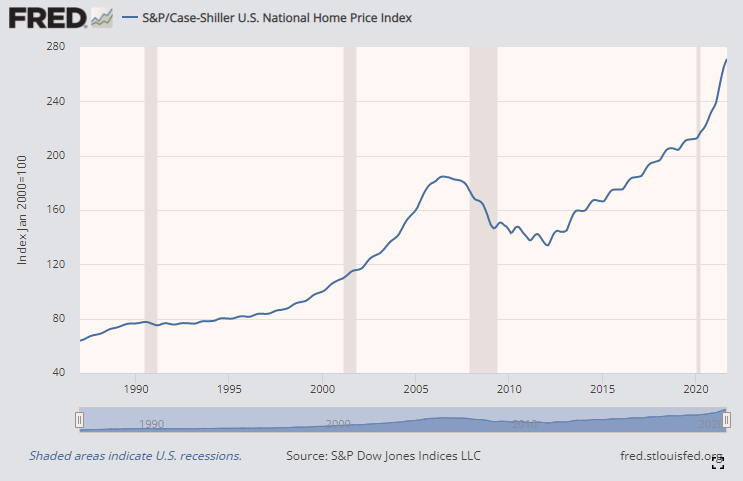

Recently Jerome Powell admitted that the word ‘transitory’ is no longer appropriate when talking about inflation, but at the same time the Fed appears to be in no rush to increase interest rates. In fact, despite the stock market and the housing market being at or near all time highs, the Fed thinks the market still needs >$100bn of liquidity injection per month. The Fed will be buying $105bn of treasury and mortgage-backed securities in December (down from $120bn in November). Quantitative easing is expected to continue into mid-2022.

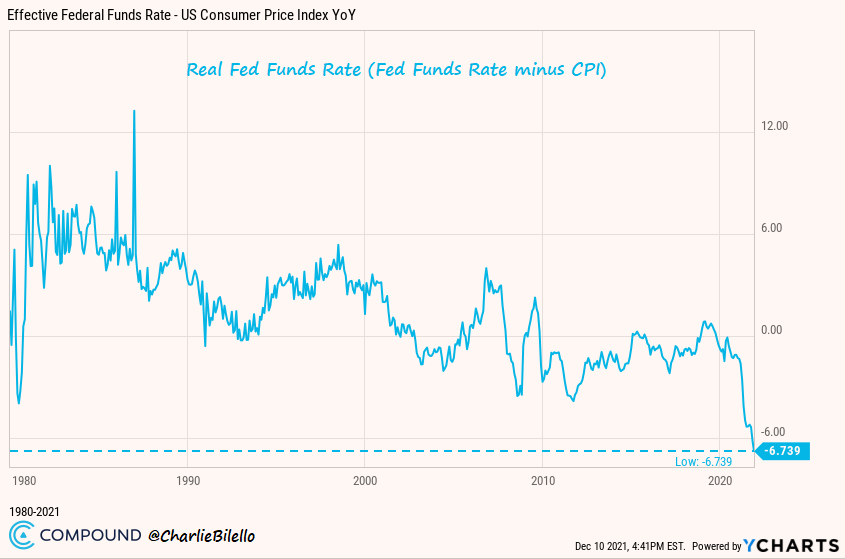

The current ‘real’ Fed Funds rate is now deeply negative, and the lowest in 40 years.

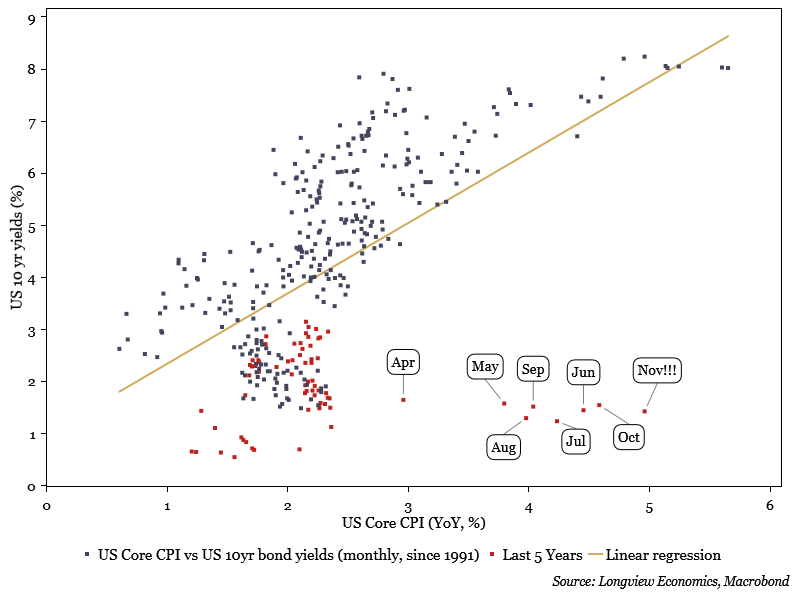

Treasury yields have also become deeply disconnected from the historical relationship to inflation (see regression below). This perhaps indicates that the gradual increase in indebtedness over the past ~50+ years has led us into a new paradigm where interest rates can’t be raised without severe financial and economic repercussions.

The Fed now faces a conundrum which many smart / prescient people saw coming many years ago: If the Fed keeps interest rates at near zero it risks inflation getting out of control and the stock market and housing bubbles to continue expanding to even more dangerous levels. On the other hand if the Fed starts hiking it risks a major economic correction given the high level of indebtedness in the economy and high duration in financial assets.

It’s important to remember that the financial market response to interest rate hikes is more sensitive to rate of change vs. the absolute level of interest rates. A 1% Fed Funds rate might seem low on an absolute level, but represents a 4x increase from current levels. To put this in perspective, it took the Fed 3 years (2015 to 2018) to gradually normalize rates from 0.25% to 2.5%, and even then the markets ‘cried uncle’ in December 2018 with a ~20% drop in the S&P500 and the Fed had to put its rate increases on hold.

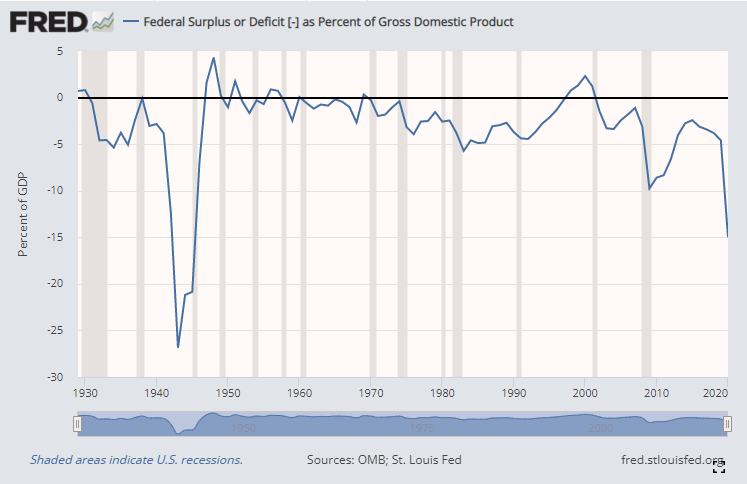

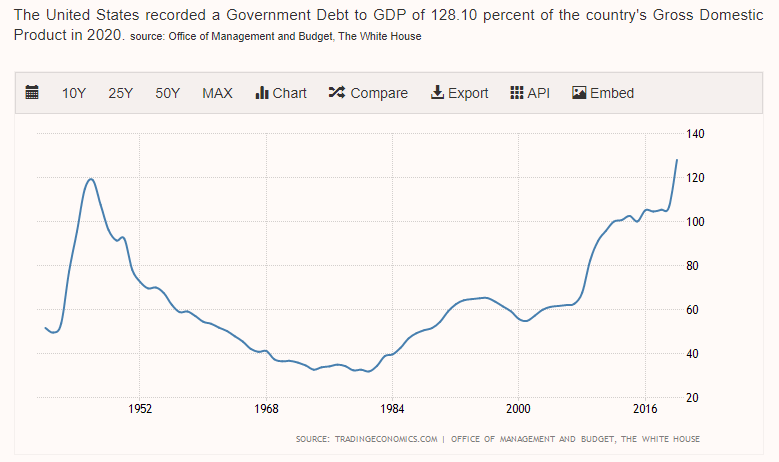

Rising rates will also make financing the fiscal deficit and rising debt levels a much bigger problem. The US is currently running the largest fiscal deficit since the WWII period with a $3t+ deficit in 2020 and 2021 and a $1tr+ deficit projected for 2022:

Debt levels have also risen to record levels with US government debt to GDP at >120%, another post WWII record:

Fed interventions in the corporate credit markets have led to a surge in corporate debt levels, with corporations having increased their debt levels by ~$1.3tr since the start of the pandemic.

So in summary we have an economy where inflationary pressures are rising, but where the most important tool to fight this problem (interest rates) can’t be used due to the economy’s extreme sensitivity to changes in interest rates. The only way out is for inflation to come down on its own (i.e. hoping the ‘transitory’ mantra turns out to be true), but I don’t think this will be the case. Here is why.

I believe that inflation over the last few decades has been low primarily due to four key reasons (in no particular order):

1/ Low velocity of money circulation

2/ Globalization (China in particular) as a global deflationary force

3/ Bear market cycle in commodities resulting from over-investment in capex during the last cycle

4/ Technology

While I do believe that some of the drivers of inflation are transitory – for example pandemic induced supply chain issues and ‘revenge’ spending / ‘pent-up’ demand will eventually mean-revert – I also think we need to pay close attention to changes in the above four ‘structural’ factors which could impact price levels for years to come.

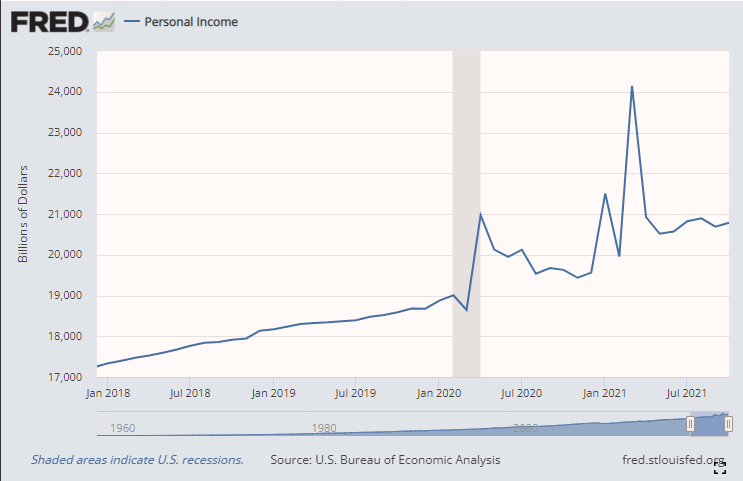

Let’s start with velocity of money. Rising asset prices combined with stagnant real wages and a lack of fiscal stimulus to supplement the Fed’s easy monetary policies have been major contributors to the low velocity of money and low inflation of the past decade. But in 2020 we had a big shift in this dynamic with the US government spending ~$4tr in fiscal stimulus to offset the impacts of COVID-19. While a lot of this stimulus money went towards filling cash flow gaps resulting from loss of employment income, a significant proportion went directly into people’s pockets in the form of savings and household de-leveraging.

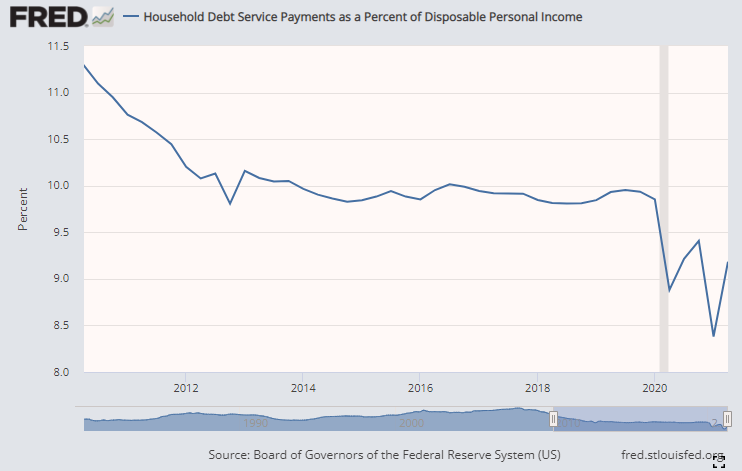

Household debt servicing costs as a % of disposal income have taken a significant step lower thanks to low interest rates and manageable debt levels. Meanwhile personal income continues to grow at a healthy rate as a result of the stimulus checks, generous unemployment benefits as well as rising wages.

Combine this with increased retail participation in the stock market, crypto boom and rocketing home prices and you can see how, for the first time in a long time, the average US consumer feels empowered to spend more.

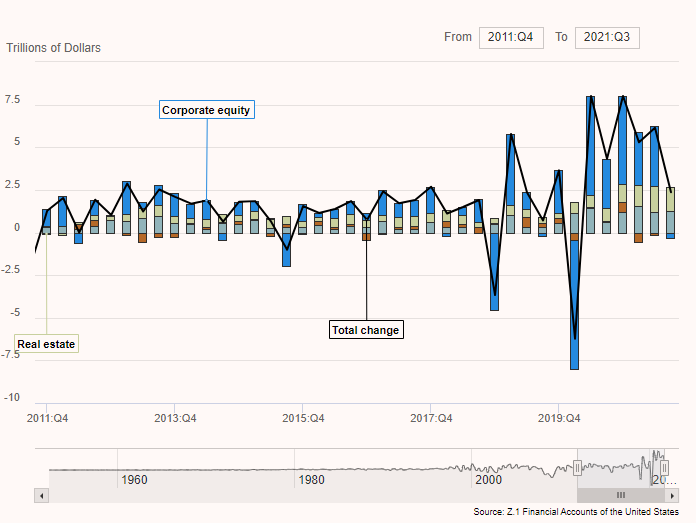

Change in household net worth from Q4 2011 to Q3 2021:

Since the Q1 2020 stock market crash, household net worth has sky rocketed and this is impacting not only personal spending, but also workers’ negotiating leverage with employers. After a very long time it feels as if the balance of power between capital and labor is shifting more towards labor with people quick to quit jobs (the ‘Great Resignation’) and increasingly reluctant to take on jobs that don’t pay the appropriate salary and benefits.

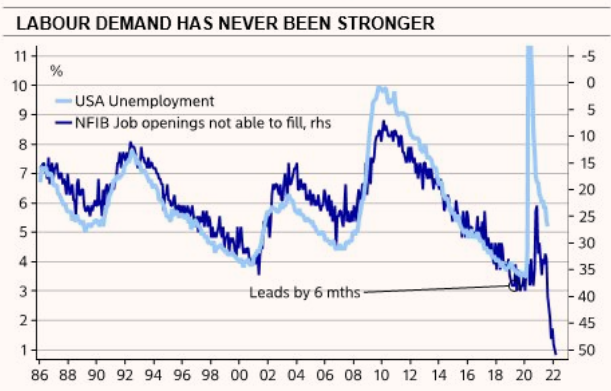

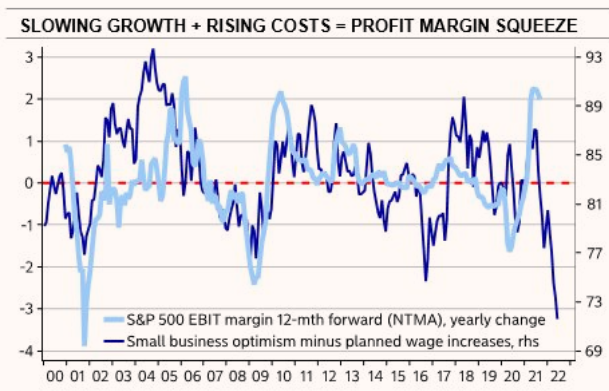

The National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) conducts surveys of small businesses to assess labor demand, wage pressures etc. amongst other things. The results of a recent survey are quite illuminating as Nordea Bank summarized in the following four charts:

This data combined with the Biden administration’s plans for spending hundreds of billions on infrastructure and green energy suggests to me that the demand for labor and upward wage price pressures might be stickier vs. the past.

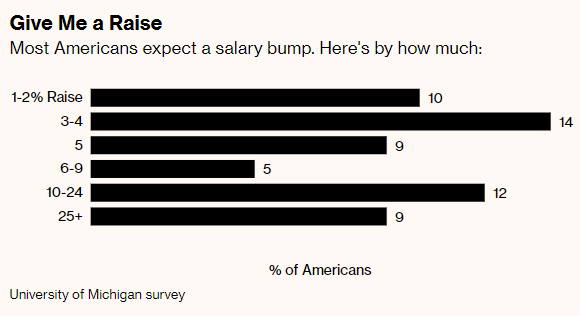

A recent survey by the University of Michigan shows that 1 in 5 Americans expect a wage increase of 10%+ next year. If workers are able to successfully secure such wage increases, expectations of wage increases could get embedded in their psychology leading to more consistent wage increases year after year, which eventually feeds into the prices of goods and services. This would lead to structural, multi-year upward pressures on inflation.

To summarize, the large financial asset bubble combined with significant changes to fiscal policy and labor markets could mean a structurally higher velocity of money as the lower and middle classes feel empowered to spend more and catalyze a wage-price feedback loop. This could make the current inflationary dynamic very different from the dynamic last decade.

Turning our attention to globalization, it’s no surprise to anyone following global markets that globalization is in retreat. Foreign trade as a % of global GDP peaked in 2008 at ~61% and recently took a sharp turn lower catalyzed by the US-China trade war of 2019 and further exacerbated by COVID-19 which exposed supply chain dependencies and increased calls for more ‘in-sourcing’.

Take semiconductors as an example. Currently the majority of semi conductor fabrication happens in Asia with Taiwan and Korea having a large share. US semiconductor companies have chosen to go ‘fabless’ and outsource manufacturing to companies like Samsung and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSM). This poses risks in the event of a US-China conflict (given China’s close proximity to these critical manufacturing facilities). Nvidia (NVDA), for example, is a fabless semiconductor company that is reliant on TSM to make their chips.

Recently Intel has agreed to invest in the development of new fabs and has been pushing the US government to provide subsidies to chip manufacturers who choose to do so domestically. Moving semiconductor manufacturing back to the US will increase resilience, but also increase price pressures. Facilities like the proposed Intel fab cost hundreds of billions of dollar to develop and require highly skilled labor to build and operate which will cost more in the US than in Asia. There are many such examples under Biden’s ‘Buy American’ and ‘Make It In America’ mantras, but they will only be accomplished at the cost of higher end-prices to the consumer.

Despite the political pressures to in-source, a lot of manufacturing will continue to be outsourced to places like China. But even there, important demographic and socio-economic changes are threatening the labor cost advantages that once acted as a strong deflationary force.

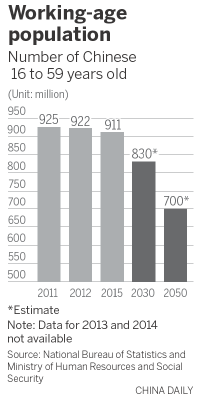

As China lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty over the last couple of decades, its population started demanding more than just basic sustenance. Wages in China are on the rise and workers are demanding more pay, more benefits, better workplace environments, less pollution etc. All of these are exerting upward pressures on the cost of production in China and are likely to continue as China pursues its ambitions to become a consumption-driven economy vs. being reliant on investments, manufacturing and exports. On top of this, China’s birth control policies have led to a significant demographic headwind that the government is trying to reverse but will likely take decades to accomplish.

This year China allowed couples to have three children, up from the two child policy initiated in 2015. However China’s birth rates have been stubbornly low as couples have found it difficult to afford raising a family with rising property prices, cost of living and environmental issues. This is the impetus behind China’s recent focus on the idea of ‘common prosperity’; the idea that corporate wealth should be redistributed and some essential services like online learning should no longer be under a ‘for-profit’ model. Environmental and worker safety issues have also been on top of mind. Some would argue that the recent Evergrande saga signals the country’s willingness to let the real estate bubble ‘pop’, trading short term financial / economic pain for longer term stability and affordability in the real estate markets.

Keeping all of this in mind, it’s hard to argue that China will continue to be a source of plentiful cheap labor for the world to fulfill its manufacturing needs. There are other countries like Mexico or India that might work as alternatives, but it’ll take many years for these countries to develop the necessary infrastructure and train their labor force to displace Chinese manufacturing prowess in any meaningful way.

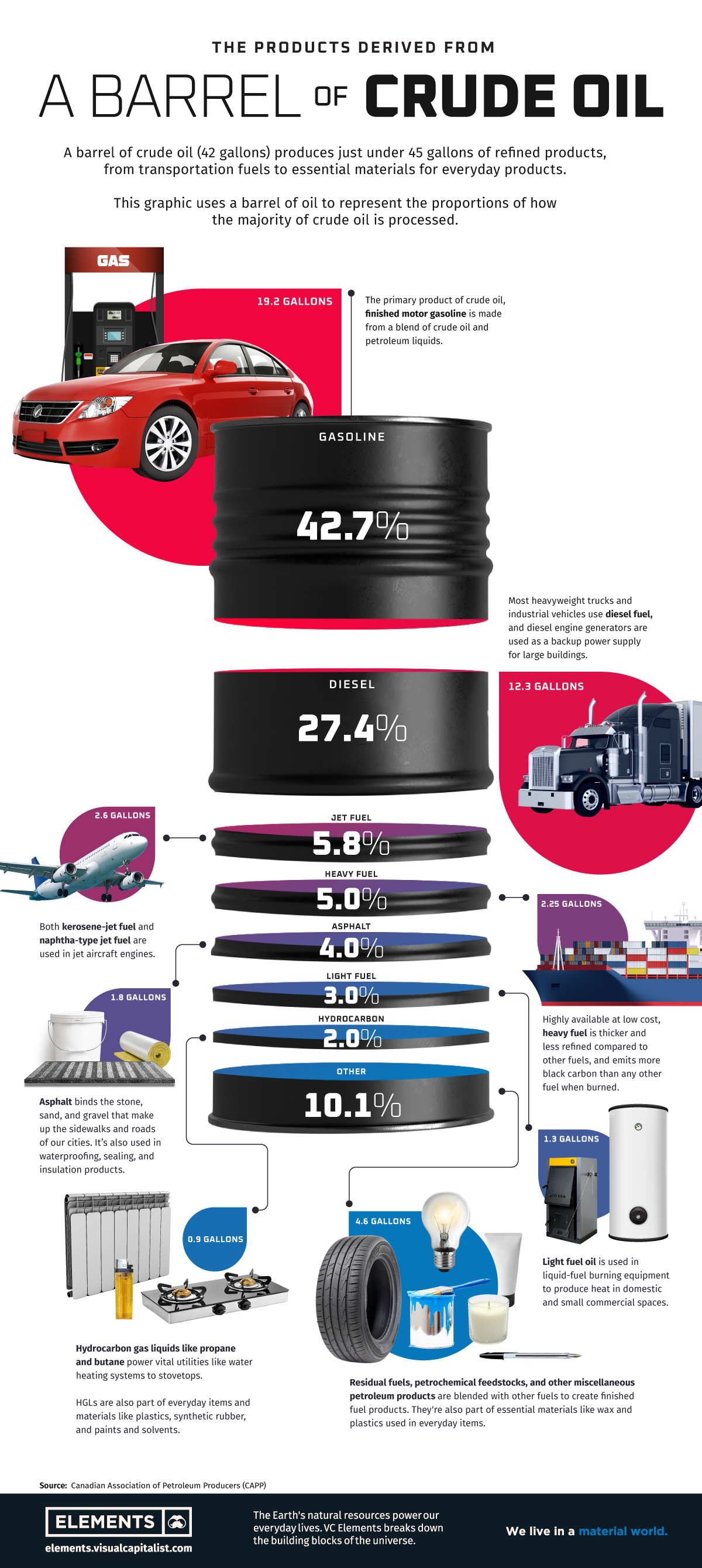

I won’t say much about energy prices here since most of the content on this blog has been focused on the impending energy bull market. But I will share a chart and a graphic that makes it clear how important oil is to the inflation puzzle. This chart from Lyn Alden (lynalden.com) shows how inflationary periods are usually accompanied by oil bull markets:

And this graphic from Visual Capitalists illustrates why this is the case. While most people think of oil as the fuel that powers cars, jets and ships, the bottom part of the graphic makes one realize that oil touches pretty much every part of our lives. Whether its asphalt in road, plastics, paint, synthetics, rubber.. you name it – it all needs oil to be produced. Higher oil prices therefore flow through into the price of pretty much everything you pick from the shelves.

While I believe technology will have a role to play in dampening the impacts of some of these factors – given the nature of inflation expectations, demographics, geopolitical shifts and commodity cycles, I doubt that the current progress in software, AI and digitization as a whole will be enough to offset structural inflationary pressures. I remember some tech folks telling me several years ago that oil prices were doomed because AI-based software would make oil exploration and extraction significantly easier and cheaper going forward. However, recent developments in the US Shale sector demonstrate that software can’t overcome the limitations of geology and the capital intensive nature of finite resource extraction. Progress in the world of bits and bytes doesn’t always translate into the world of atoms and molecules. And the latter is what the goods we consume are made up of.

Conclusion

The Fed is stuck between a rock and a hard place. If it continues its current policy, it risks losing credibility and hurting the well being of ordinary people as inflation eats away their spending power. Also, given the structural nature of inflationary pressures as described above, the Fed would risk getting inflation expectations out of control. On the other hand, raising rates will almost certainly lead to volatility in financial assets, credit contraction and potentially a recession. Given the high levels of debt in the system, there is a possibility that something could ‘break’, leading to systemic risks. As of this writing, a number of interest rate sensitive growth stocks have dropped 50%+ below their recent highs. While the broader indices have been stable, there is a lot of financial pain underneath as pretty much the entire basket of non-profitable growth stocks has been re-rated lower. If the Fed chooses to accelerate its tapering and hiking timeline, there will be a lot more pain to come. Ultimately if I’m right about the structural nature of inflationary pressures, the pain will be a lot deeper and unavoidable.